Excerpts

(twPossiplexPage-D29w)

from Possiplex-D28s

10.10.14

© 2010 Theodor Holm Nelson. All

rights reserved.

now

available at Lulu.com, hither--

Paper copy $29.99

Download $9.99

![]()

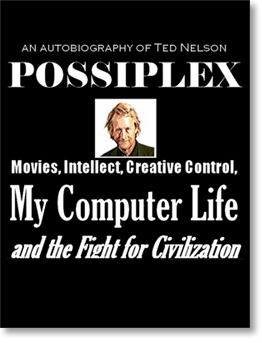

Excerpts from POSSIPLEX.

AFORETHOUGHT

[preface]

Everybody

wants to tell their story; I have special reasons. I have a unique place in history and I want

to claim it. I also want to clear the

air, substituting the true story for myth and misunderstandings about my life

and work.

This

is not a modest book. Modesty is for

those who are after the Nobel, and that chance (if any) is long past. This is what I want known long after. Like Marco Polo and Tesla in their

autobiographies, I am crazed for people to know my real story.

What

the hell gave me the background and temerity to think I could design the

documents of the future, and indeed conjure a complete computer world, on my

own and with no technical credentials, when no one else in the world even

imagined those things? And why do I

still stand against thousands of experts who want to impose their own worlds on

humanity? And why do I think I know the

true generalization of documents and the true generalization of structure, when

they don’t?

That’s

what this book is about: how I came to the visions, attitudes and initiatives

which have driven me for the last fifty years, and drive me still to keep

trying though at first I haven’t succeeded.

I am

a controversial figure, which means those who know my name either love me or

hate me, mostly the latter. Most seem to

regard me as a raving, ignorant, unconscious, delusional dreamer who was

strangely and accidentally right about a remarkable variety of things.

I was

never ignorant and there was no accident— I knew ten times more fifty years

ago, when I started in computers, than most people think I know now. I considered myself a philosopher and a

film-maker, and what I knew about was media and presentation and design, the

nature of writing and literature, the processes of technical analysis and idea

manipulation, and the human heart. I

also knew about projects, and why one dares follow the inner urgings of a

project, going where its nature wants to go.

I saw

in 1960 how all these matters would have to transpose to the interactive

computer screen. And I have been dealing

with the consequences, including both the politics and the technicalities,

straight on through since then.

• For five years I designed documents and

interfaces for the interactive computer screen without ever seeing an

interactive computer screen, but I understood perfectly well what it would be

like, imagining its performances and ramifications probably better than anyone

else.

• For five years I

worked on interactive text systems without knowing that anyone else in the

world imagined such things.

• For eight years I

worked on methods for ray-tracing and image synthesis, without knowing anyone

else imagined such things. (Now the film

industry revolves around them.)

• For at least a decade

I was designing hypertext structure without ever seeing a working

hypertext. But I knew perfectly well how

it was going to feel.

• For fourteen years I believe I was the only

person in the world who imagined a world of personal computing as a hobby,

everyday activity and art form—all of which I presented in my book Computer Lib in 1974— months ahead of

the first personal computer kit, which started the gold rush.

• For nearly TWENTY years (until I convinced

five colleagues), I believe I was the only person in the world who envisioned

millions of on-line documents, let alone on-line documents being read on

millions of screens by millions of users from millions of servers and

publishable by anyone. Not only did no one

else imagine it, I could not make

them imagine it, though I lectured and exhorted constantly.

You

might think this would give me a reputation for foresight, but many consider me

a crank because I haven’t gotten on any of the bandwagons— Microsoft, Apple,

Linux, or the World Wide Web.

Why

have I not joined any of these parades? Because they’re all alike (heresy!), and I have always had an alternative. I don’t like their designs—what you see

around you—and I still intend to get my designs running, so you can at last

have a real choice. (Unfortunately most

people don’t realize the computer world has been designed, so that’s an uphill battle.)

I

believe my standing designs for a real alternative computer world— complete,

clear, and sweeping— are better, deeper and simpler

than what people now have to face every morning.

THE

MYTH OF TECHNOLOGY

The

world is totally confused—everyone uses the word “technology” for PACKAGES AND

CONVENTIONS-- like email, Windows, Facebook, the World

Wide Web. These all use technologies but are themselves just collections of design

decisions somebody made without asking you. I see humanity as unknowing

prisoners in systems of invisible walls— specific conventions created by hidden

tekkies, sometimes long ago and never questioned since, by anybody. The myth of technology is the myth that the

software issues are technical; whereas what matters is communicating to the mind and heart of the user, and that is not a technical issue

at all.

I am certain

my designs, in part and whole, as well as the story told here, will someday

vindicate me (what a pisser! To have to seek vindication at the age of 73). But I can’t wait till I’m dead to tell the

story and I can’t wait till I’m dead to make the software work; I want to

implement these designs now, while

they can still be done right (with my own detailing), and reduce people’s

computer misery and quadruple the usability of computer documents. I want to improve the world that is.

This is a multithreaded story. I

wish I could tell it in a decent electronic document—a Xanadu document of

parallel pages with visible connections--

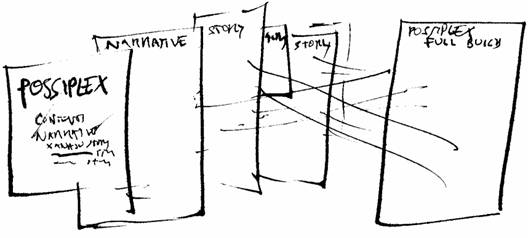

HOW THIS DOCUMENT OUGHT TO LOOK WHEN IT OPENS (links

not shown, only transclusions).

A proper parallel

hypertext in a possible opening view. The reader is able to read the full

build (right), corresponding to this assembled book, or separate narratives and

threads. Visible beams of

transclusion show identical content among separate pages (stories, threads, and

full build). Where are the

visible beams of connection in Microsoft Word, Adobe Acrobat, the World Wide Web?

Unfortunately

we have still not got decent documents working and deployed. (Part of the problem is that people don’t

understand why they need parallelism, let alone transclusion and multiway

links.)

Trapped

here on paper, I am simulating this parallelism clumsily.

…

I do

not embrace the World Wide Web, though many think it

was my idea (my idea was better). Most

people imagine that the Web is a wonder of technology, whereas I see it as a

political setback by a dorky package. (As stated elsewhere, it is not

technology, it’s packaging and conventions.)

To me

the World Wide Web is an unfortunate presence which must be dealt with, like

the Internal Revenue Service. It's all

right for shop-windows, but not for the precious documents and thoughts of

mankind, which it smashes into sequence, hierarchy, rectangularity, fixed

views, huge wasted screen-space and locked lines of text (usually far too wide

and in faint unreadable sans serif). The

Web offers no way to underline, no way to make marginal notes (let alone

publish them), no way to make visible links between the documents, and other

profound defects I won’t get into yet. And it cannot be fixed. The embedding of markup is a one-way ticket

to hell.

The

alternative is still possible. And simpler.

…

Chapter 1.

…

My

Family

Our apartment in

We lived,

Jean and Pop and I, in

I had been left at

six months’ age with my grandmother and grandfather, and named after him. These were entirely the right decisions. (I was Theodor Holm II, said a membership certificate

on the wall).

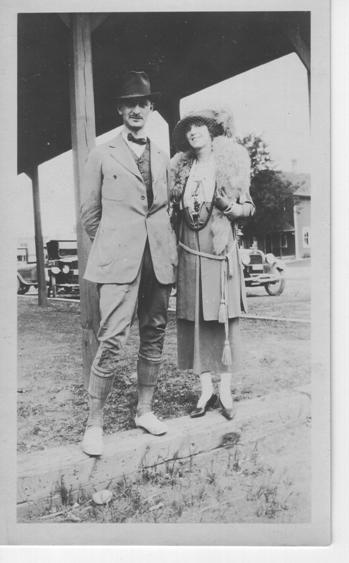

Jean and Theodor

Holm (I am calling him Pop) were an elegant couple. She generally wore high heels and a veil; in

colder weather, furs. He was dignified,

warm and thoughtful, and wore a fedora. Both spoke with what people mistook for

English accents, but she was from

My family was very

cultured and loving. Ours was a home of culture. We were members of the Art Institute of

Chicago-- actually I, in my crib, was

the member; when my grandmother went to buy a membership for the family, the

person at the desk suggested getting the membership in the name of the youngest

member of the family, and I, the newborn, was it. So said the certificate on the wall-- the

life membership in the Art Institute of Theodor Holm II.

Leonardo, Shakespeare, Shaw were our household gods;

Shakespearean quotes were bandied about frequently. There were family tales of contacts with

Gurdjieff and Tagore, and memories of a debate Jean had had with Emma

Goldman. (By "debate", I

assume what happened was that Jean asked a question at a lecture by Goldman, and

then there was some follow-on banter between them. I bet I could even reconstruct it, plausibly,

but that is another story.)

Jean and Theodor Holm at their grandest, possibly on their wedding trip to

I had four main grownups. I lived with Jean and Pop in

The author's

great-grandmother, Mrs. Edmund Jewett, née Blanche Eugenie Newell.

The author's

great-grandmother, Mrs. Edmund Jewett, née Blanche Eugenie Newell.

Edmund Gale Jewett, Blanche’s third husband, was not

actually my great-grandfather; she had been twice widowed before marrying

Edmund, but we called him my great-grandfather out of courtesy and love.

*Smith and Jewett, An Introduction to the Study of Science,

Macmillan (originally published 1917).

Edmund Gale Jewett (the author's great-grandfather, on

the right) with his workmen at the Lain-Jewett Dry Kiln Company, ca. 1908. His beard was red then. We see the helical heating pipe being

assembled. It says on the back, “

Edmund was a science teacher, very reserved, with a

white beard. He had invented the

fundamental method of lumber-drying now in use, but the big lumber companies

had stolen his invention and he got nothing for it. The 1920 edition of his science book,* still

very good, is available for download (now copyrighted by Google).

*Smith and Jewett, An Introduction to the Study of Science,

Macmillan (originally published 1917).

Edmund was to teach me about evolution, astronomy (his

great love), physics, algebra. But he

also wrote beautiful poetry. One of his

poems about evolution, written in the thirties, is still precisely accurate

within today’s knowledge. My four

grownups all treated me with great love and respect. In an early, hazy memory, I recall the four

of us-- Jean and Pop, Blanche and Edmund—in the lower cabin at the farm,

perhaps on a summer evening. When I

would speak they would all fall silent. By the way they listened, they told me

that I was very clear-minded, that my thoughts were special and that I

expressed them very well. That is how I

first learned who I was.

Many children fantasize that their real parents are

faraway, glamorous people. For me this

was actually true. Like Harry Potter, I

had magical parents who were not present, and like Harry Potter I have been

greatly punished for it. But that is

another story.

My parents were young actors who needed a divorce

almost immediately they were married, but my grandfather made them stay married

until I was born so I would be "legitimate." Away went my parents to their separate

remarkable destinies, but each would visit, separately, a few times a

year.

Jean and Pop already had a rich history. On the eve of World War I, she headed to

Europe to document the coming war with her drawings, buying a ticket on the

However it may seem to you, I did not think I was having a

privileged childhood. There was so much

I could not have. And there was so much

I did not like, especially school.

School

My

school, the

I do remember the day I learned to read. I knew the alphabet, of

course, and we had been learning to spell words, but it had never been all put

together for us. And I had not been

pressured on the matter. On this day

Miss Ferlette, my lovely first-grade teacher, handed each of us a pamphlet with

a different story. (They were

photo-offset in dark blue, as I recall.)

Now the words were in a row, and I saw how they were put all

together, and I read the story, and the excitement filled me.

Miss Ferlette was very pleased when I asked for another.

She was especially pleased when I asked for a third.

CYNICAL

AND OUT FRONT: the author, 4, leads kindergartners debouching the school

vehicle, ca. April 1942.

Love

and

Jean

and Pop were not only elegant, but the dearest and most loving people I have

ever known. Every night at bedtime one

of them would read to me, sing to me or tell me a story. And we would read together—that is, Pop would

read, while Jean would sit or sew; I would play with my blocks or kaleidoscope,

or whatever. Pop read many books to us,

including Just So Stories, Swiss Family Robinson, and a number of

the Doctor Dolittle books. And my favorite early book, Paddle-to-the-Sea,*

by Holling.

![]()

* My earliest visions of hypertext and hypermedia, in the

1960s, were closely related to Paddle-to-the-Sea. Each of its chapters has a text, a painting,

an ink drawing, and a map. The reader (or

the read-to) unites these in the mind, learning to connect different aspects of

sight and story.

Pop

had a beautiful voice and he would sometimes read for an hour or more. Those were happy times.

Summers

at our farm, Blanche, my great-grandmother would read to me. I remember especially her reading animal

stories by Albert Payson Terhune, and the Oz books that I so loved.

…

Love

and Words

We

had a home of wonderful words.

I

loved every new word. A new word was a

gift, a lens, a construction piece. Words were my toys and my best friends. (I

also had occasional friends among children, but most of them knew very little,

though I would fall in love with the girls and have to hide it.)

We

spoke the best English in our home. I

became aware that most people did not.

“It is I,” we would say. The word

“exquisite” had to be emphasized on the first syllable, as did

“despicable”. However, we considered

“tomayto” to be an an acceptable variant to our pronunciation of “tomahto”;

many aspects of words were matters of taste.

OUR

WORDS

We

often used old-fashioned and Shakespearean phrasings, like “Art thou

hungry?” The words thither and thence, whither and whence were part of our everyday vocabulary. But only at home, between us.*

* Linguistic pride and conservatism ran in the family,

it seems. Only recently did I learn that

one of Pop’s older brothers in

We

talked about puns, spoonerisms, portmanteaux and teakettles, euphemisms and

paraphrases, idioms and clichés, synonyms and antonyms, malaprops and

misspellings, old saws and epigrams, anglicisms and anglicizations and ‘words

which have no equivalent in English.’

Newly-coined

words were always of interest, like someone a friend brings to dinner. I became aware that coining words was simply

something one did, like naming

children or pets.

I

realized: Every idea needs a good word to swing it by.

The War Begins

Though

I was only four, I remember the beginning of World War II. I was in Pop's lap, and we were listening to

the symphony on our cathedral radio, when the program was interrupted with the

news that the Japanese had attacked

After

Ralph Nelson, visiting father, dandles

the author (left); probably spring 1943.

…

![]()

Flowers by Wire

(Data Structure,

~1942)

I was five. Jean, my grandmother, often took me to flower

shops in

How did they get the flowers down

the wire?

I asked the flower-man how Flowers

By Wire worked. He said, ‘Oh, you

wouldn’t understand.’

The flower salesman wouldn't tell

me, so I tried to figure out myself how they sent flowers by wire. I thought about it and thought about it. It was a hard problem.

Would they start with the stems

first, or the petals? And what about the

aroma?

I knew, obviously, that you could

send a voice by wire; evidently flowers could somehow be sent as well.

I understood how phone calls went

through the wire—there was something you talked into (I didn’t yet know that it

was called a microphone) that translated the speech into some sort of event (I

didn’t know the term “signal”) that went all the way to the other end, and

there was something else (I didn’t know it was called a speaker) that

translated the event back into sound. So

I had a correct, if approximate, mental picture of telephony.

But how would that work with

flowers?

You would have to have some kind

of a device at each end, just as the telephone call had a device at each end.

I figured that the device at the

starting end must take the flower apart, probably by grinding off a little at a

time, and converting that into a signal which went down the wire, and then

grinding till the whole flower was transmitted. And then at the other end there

would be a device that reconstituted the flower fragments from the signals, and

perhaps extruded the flowers like spaghetti.

But would they start with the

stems first, or the petals? And what

about the aroma?

These were difficult issues, but I

felt I had a handle on the basics.

I believe these were my first

deliberations about data structure, and that the analysis was rather good

considering the information I had—in fact, that’s how many systems of scanning

and transmission work today. But not for

flowers.

If you had told me the real

answer-- “How do they send flowers by wire? Someone at the first flower shop

telephones the second flower shop, and asks the person at the second flower

shop to deliver a bouquet to a specific address,” I would have been outraged

that the flower-man withheld such a simple, stupid fact.

Still, it was a

thinking and learning experience.

…

![]()

My

Hand in the Water (~1942-3)

I trailed my hand in the water as my grandfather rowed. My

grandmother was in the front of the boat, wearing high heels as always. I was four or five, and this was spring 1943

at the latest; we were still in

Fuzzy shapes passed underneath. I studied the water's crystal

softness. The water was opening around my fingers, gently passing around them,

then closing again behind.

I considered the different places in the water and the connections

between them, the places that at one instant were next to each other, then

separated as my fingers passed. They

rejoined, but no longer in the same way.

How is it, I wondered, that every instant's arrangement, in the

water and the world, can be so much the same as just before, and yet so different?

How could even the best words express this complexity? How could even the best words express what

systems of relationships were the same and different? And how many

relationships were there?

I could not have said "relationships" or

"systems" then, let alone “particles” or “manifolds” or

"higher-level commonalities," but those were my exact concerns. My

questions and confusions were always exact, and fine distinctions concerned me

greatly. They still do. In this book I will try to say exactly what I was

thinking at different times: exactly, that is, in my vocabulary of now.

And how, you might ask, do I remember those floating swirling

thoughts over sixty years ago? Because these

are matters I have thought about ever since, in thousands of different ways,

and I reconnect them even now with that early moment of floating crystalline

study, rattle of oarlocks, sun-twinkle on the water, my grandmother clearing

her throat, the thump of oars, my grandfather's earnestness; all with me as I

write in the eternal Now and Then.

![]()

CONNECTION TO THE ORIGINAL (1)

That religious

experience, the moment of my hand in the water, is with me always. Always I see the profusion of relationships,

of connections, of ideas, of possibilities, as a great net across the world,

across every subject, across everything.

All my philosophical

thoughts since then derive from that insight in the rowboat, or perhaps some

fundamental pattern in my mind that first projected into the water, some strip

of mental film projecting outward from my inner center, from which that insight

came.

The insight was

sound. Profuse connection is the whole

problem of abstraction, perception and thought. Profuse connection is the whole

problem of expression, of saying anything.

It is the problem of writing. It

is the problem of seeing-- we see and imagine so much more than we can

express. Trying to communicate ideas

requires selection from this vast, ever-expanding net. Writing on paper is a

hopeless reduction, as it means throwing out most of the connections, telling

the reader only the smallest part in one particular sequence.

And this is what I

have hoped to fix, or at least improve, through most of my life, giving the

world a greater and better way to express thoughts and ideas. And that is what this book is about. This book is about the story of my life and

thoughts, and of connections, and it is about the connections all-amongst life

and thought, and how I have fought to bring about a better world of thought and

its representation.

The Wonderful

Future

My

abiding interest was in the wonderful future and how great it was going to

be. Everything would be all chromium and

Art Deco; no longer would there be wood, or baroque curly decoration. Homes would be starkly rectangular. Robots would attend to our needs and whims. Automatic cars would take us everywhere on

the ground, but rocket packs would take us further. Most of the time we would be off the planet,

in spaceships.

Mainly

everything would be different, and much, much better.

…

![]()

•Interaction ![]()

DESIGN INFLUENCES: Interface Horrors

The Exploding Pressure Cooker (~1946)

Pop loved his new pressure cooker,

but one night he opened it without letting the steam off. My beloved grandfather was nearly killed as

the heavy metal top flew past his head; his face was scalded by boiling-hot

mashed potatoes; he would have been blinded except for his glasses, which were

covered with boiling-hot mashed potatoes.

On the long drive to the country

hospital, as my grandfather whimpered beside me in the back seat of our Model A

Ford, I was filled with rage at the idiots who had designed that machine; even

a nine-year-old—hell, even a five-year-old! could see how it could have been

designed to be safe, making sure the pressure was released before you opened

it. The designers chose instead to build

a machine that could punish absent-mindedness by death. What fools! What bastard fools!

![]()

This was my searing introduction

to interface design, and to the stupidity it invites.

The guys who designed that

pressure cooker—or their spiritual heirs-- are in the computer business

now.

![]()

I

Become a Bohemian (1946)

Our home-room teacher in fifth grade was Mr.

Vanderwall. We all loved him. He was playful and fastidious about

language. If you asked him for a “piece

of paper” rather than a sheet, he would tear off a corner and give it to

you. He drilled us on the correct spellings

of “supersede” and “surreptitious”.*

* How many fifth-graders today have

even heard these words?

I was less fond of Mr. Bessenger, who taught us Geography

for 15 minutes on Monday, Wednesday and Friday. (Mr. Bessenger was renowned for

throwing books at students, but I never saw this.) All I remember of Geography was that Mr.

Bessenger wanted us to recite the forty-eight states in one breath. I don’t remember whether I made it. On Tuesday and Thursday, in the same

15-minute slot, Mr. Bessenger taught us Opera.

* Now, you may think it strange

that there was a course in Opera, and thinking back, so do I, but all courses

are strange to kids, so who knew?

This consisted of having to learn the plots of famous

operas. (I still have the little book of

the 100 plots.) When we got to "La

bohème", the book said it was aboht Bohemians. I asked, reasonably, “What is a Bohemian?”

“Look it up,” said Mr. Bessenger.

Surprisingly, the school library had the original novel (in

translation) from which the opera had been taken— Scènes de la vie de bohème by Henri Murger, as well as some history

of bohemianism in .America.* I read

these.

* Apparently not the Parry volume

of that title, since the book also made me a great admirer of Joe Gould, whom

Parry treats disparagingly. The very

best such history now is Republic of

Dreams, by Ross Wetzsteon, but that was written much later.

The history said that Bohemians were free spirits who were

uninhibited about life and sex, and unfettered by middle-class

conventions.

I already felt very fettered by middle-class conventions—

especially the tension in the elevator of our apartment building, where we had

to discuss the weather with other people in suits— and this sounded fine to me.

I decided: I’m going

to be a Bohemian!

The book said that the center of Bohemianism in

* Some readers will be amused to

recognize that

Bucky Says It All

(1947)

Bucky Fuller believed we could have a new and much

better and very different world.

This gave me something to hope for in a world I rather

disliked. (I have always believed life should

be completely different.)

He said the educational system was horrible—I totally

agreed; and he wanted to fix the world by design—the

design of his magnificent car, the design of his house that would come in by

helicopter and be lowered on a pole.

Buckminster Fuller was my hero ever since.

Sophistication,

Age 10

I believe that at the age of ten my favorite word was

“ostensibly.” I know I could recite

Hamlet’s “To Be or Not To Be” and a few verses of the Rubaiyat; I could sing, write

out (and accentuate correctly), numerous songs from Gilbert and Sullivan, the

first verse of the “Marseillaise” and all four verses of the Star Spangled

Banner.

Such it was to be a literate child in the

nineteen-forties.

![]()

I believe that at ten I could have told you who had

coined the words “tintinnabulate”1, “chortle”2, “robot”3,

“serendipity”4 and “dymaxion”5.

1Poe.

2Lewis Carroll.

3Karel

Capek.

4George

Eliot, and I would have been wrong. Now

I have learned it was Horace Walpole.

5Bucky

Fuller, and I would have been wrong. It

was coined by Waldo Warren, who also coined the term “radio”.

I was

not a prodigy. I had no special

direction. I was just very clever,

high-strung, interested in a lot of things, disgusted with school and middle-class

life, and a lover of reading and movies and ideas.

![]()

No one could have known, least of

all I, that this bundle of traits would define the direction of my life.

…

![]()

Nexialist , 1950

I

found a wonderful word in a science-fiction novel. In van Vogt’s Voyage of the Space Beagle, he defined a

nexialist as 'someone who finds connections.'

I typed up a

business card

Ted Nelson

Nexialist

and filed it.

.

My World, End of

High School

Here is how the world looked to me then:

I was a New Yorker. I was

sophisticated. (The denizens of the

midland states, like

My favorite words were “concomitant” and “societal.” These were not showoff words, you could only

use them if you needed them and knew what they meant. I also loved jokey words I had found in the

dictionary, “transpadane” (meaning “on the far side of the

The three pillars of my identity were:

• The New Yorker-- deep sophisticated

journalism far above what most people got to see.

• The

• The Rand Corporation, which I had heard

about from Leo Rosten. I was deeply

worried about nuclear war, and that is where they made the policy; I felt I

might contribute. (I only found out

decades later that due to their own snobbery,

*One of the big magazines— The Saturday Evening Post or Collier’s-- ran an incredible issue

about a hypothetical nuclear war, which I read carefully. It had a vaguely happy ending—though

But to the

The enemy was

=== Summer of 1955

(I turned 18)

Onstage with Name

Actors

For the summer of ’55 I went to a training theater in

Ralph was also up there with his new family; he was directing a

production of “Picnic” with Eva-Marie Saint. I played little parts at the

training theater, but twice I was given parts on the main stage, due to Ralph’s

influence (I realize now). I was given a

walk-on in “Member of the Wedding” with Ethel Waters, and played the court

stenographer in “The

I enjoyed being onstage, and felt comfortable, and loved the

company of actors, who were in general outgoing, often boisterous.

But then college began, and that all was swept away. I forgot about the stage in the excitement of

my new surroundings.

Chapter

4.

SWARTHMORE

ERA, 1955-59

Seeker After

Truth

Swarthmore was nothing like my previous experience of

school. School, for me, had been horrible

for fourteen years. I hated school from

kindergarten through high school. (What does that say about the educational

system? Why must the first years be

horrible? I am sure they are for the

majority of students.)

But now this was exciting. My mind was a bird set free. There were wonderful new words on every side,

exciting conversations wherever you were, free lectures only a short walk away.

I could choose my courses, and was surrounded by smart

kids on a beautiful campus with very nice professors you could get to know

well. In the afternoons and evenings

there were public lectures on everything—by visiting great thinkers, by the

faculty, even by students-- most of which there was no time for. Anyone could give a lecture and have it put on

the calendar! I once did.

What would Sam Hynes

have said? 1955/2010

I recently [March 2010] visited Sam Hynes in

“WE ALL WERE!” said Sam.

There was a legend at other schools— may still be--

that students at Swarthmore study all the time. This came about, I think,

because weekend visitors to the campus saw the students studying. But that was the rhythm of Swarthmore life—

weekends were for studying because the weeks were so busy.

At first I thought the campus would be one big happy

family, but it was harshly divided into factions—the extremes being (on one

side) the fraternities and the engineers, both well-stocked with louts from the

sticks, and (on the other side) the sophisticates and bohemian intellectuals,

many in the Mary Lyons dorms, who cynically flouted the rules about drink and

sex. The girls were divided correspondingly

between prissy-looking and promising. I

had found my

![]()

Only later did I learn

that nearly everyone on campus flouted the liquor and sex rules, but the girls

on the Bohemian side of the campus did so more stylishly.

![]()

What would Courtney

Smith have said? 1955

At the Quaker Meeting House, a place for solemn

gatherings, our class came together in its first great assemblage, to be

addressed grandly by various members of the faculty.

“Take a look at the person on either side of you, because

one of you won’t be here four years from now.” I don’t remember who said that.

“Those of you who arrived as Christians will leave as

Christians, those of you who arrived as atheists will leave as atheists.’ That was Larry Lafore, the lovable tubby

cynic and atheist historian.

But one thing was said that really hit home. Someone said, “Be a Seeker after Truth.”

[Caps mine, since I didn’t see the notes.] That hit a glowing spot inside me.

To find the truth was exactly what I intended.

I don’t remember who said “Be a Seeker After Truth.” I recently (2009-10) asked some of my

classmates. None remembered but several

thought it was Courtney. (Everyone

referred to Swarthmore’s president, Courtney Smith, as “Courtney” behind his

back.) Courtney Smith was a clip-art

college president: tweeds, pipe, thoughtful demeanor. He stayed aloof from

student affairs, leaving dirty work to the deans, but at solemn occasions would

always be impressively grave, gazing from on high.

…

Publishing A

Magazine

I

went to the organizational meeting for the college literary magazine, The Lit,

and found the students in charge very pompous. They said they were going to

have the highest, grandest editorial standards, and that the magazine would

cost eight hundred dollars to publish.

I

thought this was ridiculous. I was sure

a magazine could be published for much less.

I

went to a printer in

I

figured to do a little magazine—a very

little magazine—on one legal-sized sheet, both sides. (I would cut and fold it myself.) I was told that would cost $32.50.

I did

the magazine with a friend, Len Corwin—he contributed an off-campus mailing

address and I did most of the work. I

solicited contributions; I wrote most of it; I laid it out on big sheets; and I

paid Russ Ryan, the great Swarthmore cartoonist, to decorate the paste-ups with

his pictures.

The

result was much better than I had originally hoped for. It was whimsical, wild, and full of clever

cartoons.

It

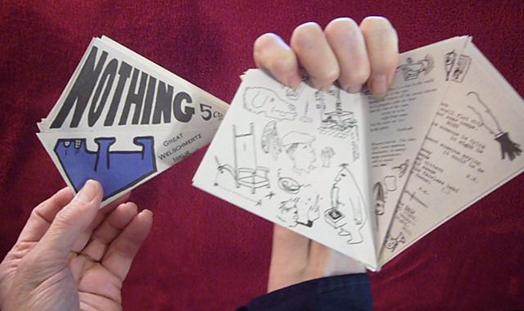

was called Nothing, and sold for five

cents. It was not just a little

magazine, but a very little magazine,

the size of the palm of your hand. (Third issue is illustrated, later.)

A lot

of people liked it. The issue sold out

and I reprinted it.

* Eventually Nothing

ran for three issues. (I later heard

“three issues” cited as the criterion of success for a little magazine, but was

not consciously trying to reach that number.)

…

![]()

NEGOTIATING POSSIBILITIES:

Nothing takes its own shape (~ Feb 1956)

I don’t remember what concept I

started with in my mind, except that it had to fit on both sides of one sheet

of paper (that was given). Then I

decided the cover (all four inches of it) should be blank. Then students from around the campus started

submitting poetry! Some of it was very

good.

Then Russ Ryan, Swarthmore’s great

sarcastic cartoonist, agreed to do illustrations. I don’t remember what I paid him, maybe $10,

maybe $25.

Ryan’s cartoons perfected the

ideat. (As they did for Nothing #3, illustrated later.)

If I had started with an exact

conception and stuck with it, the magazine wouldn’t have been nearly as

good.

From this I learned: be open to project possibilities as they

unfold; be ready to steer the project to follow your vision as required, but

take heed of where the project wants to go.

What would Victor

Navasky have said? 1956/1997

I ran into Victor Navasky, editor of The Nation, also a Swarthmore alumnus, around 1997. He said, “Not THE Ted Nelson?” I politely waited to find out what that meant

to him.

“Not the Ted Nelson who published Nothing Magazine?”

Ah, what an inner glow that gave me.

…

=== 1957 (I was 19)

A Kite-Shaped

Nothing

![]()

Later that year I put out the third issue of my little

magazine. I made Nothing #3 quite tricky—kite-shaped, and you had to rotate it as

you read it, and with two-color printing. (Again I went to Russ Ryan, whose

great drawings had so enriched Nothing #1,

and again he festooned it with marvelous, cynical cartoons. )

I showed a mockup to Ned Pyle, my friend the printer,

before we started to make the negatives, and he nodded approval; but when we

assembled the first real one he was astounded. I thought he had given me the

go-ahead for my design, but in fact I had done it all on my own.

Nothing #3 was a turning point in my life. I found out by accident that I could do stuff

on my own that nobody else could imagine.

Kite-shaped Nothing #3, showing principle of rotary reading (right). The author is still mortified at having

misspelled "Weltschmerz" on the cover.

…

Chapter

5.

NOW WHAT? (1959)

=== 1959 (I was 21)

College

was winding down. My education was about

to be interrupted by graduating.

I had

used my opportunities to the hilt—pursuing every subject (except those for

which I couldn’t do the math), and mainly extracurriculars, where I had sampled

everything and gotten the taste of creative control.

I had

not found a wife yet. I was looking for a

brilliant intellectual companion, a sexual adventurer, a wonderful mother to my

children, and an Olgivanna* to my projects.

*Olgivanna Lloyd Wright, Frank Lloyd Wright’s third

wife, was a ferocious organizer and ally in his wrangles.

I

would find them all, but not at the same time.

I was

hyperambitious, but I did not know for what. I knew a lot about media (the term

had not yet been popularized) and their creation. I was good at writing, photography, stage

direction, calligraphy; I had won prizes for poetry and playwriting, published

my own magazine and my first book, created a typefont (as paper cutouts) and

produced a long-playing record. (I had

not yet tried the one remaining medium, the one I loved most.)

I understood the different career ladders of

authorship, show business, publishing. They did not immediately appeal. (I had

a special talent for advertising, but that was absolutely unthinkable, the

quintessence of Selling Out—and while I found it fun, certainly not interesting

in any deep way.)

Most

of all I knew about projects, and about momentum. New projects were my heart and soul, and I

dared not lose momentum. I was

supercharged, but I knew how hard it was to reach that level of energy and I

knew that if I lost it, I might never get it back again.

My father had offered to start me on a career in

acting, which I had wanted all my life until college. Now I saw a bigger

world. Also, I wouldn’t be that good as

an actor. I had stage presence, but a

horrible voice and deep acne scars. I

didn’t have great acting talent—Steve Gilborn, a classmate, was a far better

actor. In the big world, there were great actors like John Barrymore and

(later) Johnny Depp; I would be embarrassed to pretend to a place in that

world.

I wanted to be the best, and to do something that had

never been done before.

THE

ACADEMIC OPTION

Of

course I would be writing and doing media, I knew not what; that was given, and

the opportunities were everywhere. But I

could not leave the intellectual world.

The

sheer excitement of all the world’s ideas still filled me. And in these four years I had found my way to

the new edges, the precipices of thought: Bruner in psychology, Whorf and other

linguists (Bloomfield, Chomsky); romantic extenders of the linguistic ideal

(Whorf, Edward Hall, Pike. What more new

ideas would be out there? (Nothing that

would get into the intellectual laymen’s magazines like Harper’s or the

I had

not learned enough, there were fields about which I knew little, and I dared

not lose intellectual momentum. I had

seen what happened to people who let their minds go to seed. And there were still so many things I had to

know in courses I hadn’t had a chance to take. Why couldn’t there be a

five-year or six-year bachelor’s?* But

in what field should I continue? In

graduate school, the enforced next step, there was no such thing as an

undeclared major, or General Studies.

You had to pretend you were going to be

something, and pretend to choose a field (though of course few people ever end

up in the field they study there).

* Answer: you actually can do this, especially at the

larger universities. But it’s not

acknowledged as a valid educational strategy, and it’s expensive. The main question is who pays. No one in my family would have backed

it.

I

thought I might get a doctorate, then teach for a while until my true vocation

was revealed.

* I did not realize what a doctorate took, but that is

another story.

Meanwhile,

anthropology interested me strongly. I

had the rough notion that I might bring to anthropology a new analytic

clarification, perhaps straightening out Levi-Strauss, the metaphysical and

sweeping theorist, with new tools of analysis and description.*

* To

non-academic readers: for academia, this was a very ambitious thought.)

…

So

But

deep down I thought I might invent a field that nobody had created yet.

CLOSET IDEALIST

I did not hang out with the big-time idealists on

campus— the religious kids, or the disarmament guys. People thought I was just flippant and

playful. In fact I had strong ideals,

but because I was a total cynic I saw few hopes for the world. I was deeply worried about nuclear war,

pollution, deforestation, the loss of books and libraries, the loss of native

cultures and languages. (These causes

have since all become fashionable, but they weren’t then.) And I very much wanted a change in the sexual

system. (In those days, unmarried women

could not get contraceptive equipment and there was no pill; anything but

straight intercourse was illegal in most states; group sex was spoken of in

horror.) All this would change, I hoped.

…

But what I saw everywhere was shallowness, conventionality,

pomposity and smugness—the Four Horsemen of Respectability.* I saw the world as run by the shallow,

conventional, pompous and smug. Those in power were shallow, conventional,

pompous and smug, and so were those who supported them.

* My term, used here for the first time.

There were so few possible hopes--

• Politics was hopeless. It was always the same circle of tricks

and speeches.

• Economics was hopeless. Communism had been horribly tried,

socialism was impossible, and our existing system (whatever you wanted to call

it) had its nasty side; but there it was, unchangeable. I also believed that capitalism offered more

hope for change and betterment than anything else. A man like Howard Hughes,

who could do what he damn pleased with his money, could take steps to improve

the world that no official charity could hope to do. (Except, of course, he didn’t. But a some do, outside official charities.)

• Philanthropy was hopeless. Official charities and foundations were

palliative window-dressing, small attempts to adjust what could not be

changed. Most important, they were

really defined and hemmed in by the tax rules, which guaranteed that they had

to be run by boards of conventional people and that they would always be shallow,

conventional, pompous and smug.

But here was the one hope I saw: there could be a cultural revolution.* And I hoped somehow to put my stamp on a part

of that.

* This was long

before the Maoists gave a Red spin to the term ‘cultural revolution.’ I had something very different in mind.

Especially, I wanted to change education. Why did the first twelve years of school—the

ones most people got—have to be so horrible? Why couldn’t the excitement of

ideas I felt in college be available to everyone? Surely there would be a way to break open the

educational prison and show how really interesting everything all was? Some way of making clear all the exciting

connections?

…

![]()

Not

Narrow Down

Here is what they said as graduation approached: It’s time to narrow

down, Ted!

I didn’t think so.

My strength was in not

narrowing down, in doing something new and different every time.

And here were my central talents, which I’d come to

know at Swarthmore: I believed I could analyze anything, show anything and

design anything. And I could innovate,

imagining what no one else could, and bringing that new thing forth through

projects of new shapes.

But what? What

should I analyze, show, design and innovate about?

There was no determinate answer. I was good at a lot of things but not a great

talent at any one (except that my mind was very good). My uniqueness was in the combination of numerous

abilities, and in my ability to see the big picture quickly.

I was a very clever fellow accustomed to picking up

new technicalities as required, but I preferred to delegate technical details

once I had decided them. I had had a

taste of creative control and knew that I could not be an Idea Man on someone

else’s projects. Deciding the details

and finishing touches was what life was all about.

I knew this would make it harder, but what the hell, I

was Ted Nelson.

I would not narrow down. That would be

giving up and giving in.

Cocteau,

Whorf, Bucky

I had very few living role models. I applauded my parents’ grand success, but I

intended some much grander career, like various great names in history. I felt I was off to a flying start.

But at what? I

was a writer and designer and showman. I

saw myself becoming perhaps--

• a showman-intellectual,* like one of my

heroes, Jean Cocteau.

* A recent nice term is showman-penseur.

• a theoretical explorer in some new area like

my hero Benjamin Lee Whorf, an academic outlier (he was in the insurance

business) who was nevertheless respected in academia, and created a field of

his own.

• like my boyhood hero Buckminster Fuller, a

“designer and thinker”.

Looking back, I

tracked on the wavelengths of these three men surprisingly well. But little did I know what this agenda had

cost Bucky, or what it would cost me.

Perhaps I could create a field of my own, like Whorf

and Bucky.

Egotistical, you say? Of

course.

But I was going to bet my life on it.

Still

a Chance to Make a Movie

My grades were fairly poor. I had gone for breadth, not depth, and I

thought it was my own business to judge my achievement, not anybody

else’s. No one would care about my college

grades in the afterlife of the so-called Real World. What mattered to me was

studying what I chose, to the degree I chose, and pursuing the excitement of

new ideas and projects.

So because of my slackness with regard to grades, and

not having done nearly enough of the reading, I was worried about

graduating.

However, something came up that was even more

important than graduating.

Late in the year I realized: I still have a chance to

make my first movie! I still have that

$700 appropriation that Tony and I got! I can MAKE that movie! Tony would have wanted me to!

Exams were coming but I figured I could squeak

by. This was far more important, a

full-on chance to make a movie by myself. I knew other media moderately well;

this would tell me whether I had any ability at film-making.

There

was no time to write a script, and synching the sound would be an enormous

problem, so I made the whimsical decision to have the actors just say “parp

parp”, and postpone writing the dialog. I would write the script later on the

basis of the film as shot, and synch it as best possible to the parping. The

parping would look like “Huckleberry Hound”, where the characters just move

their jaws vaguely to the script. It would of course look stupid but I thought

it would be funny as well.*

* It turns out most people can’t stand this; they

cannot accept such a movie as a genre, like “Huckleberry Hound” or

fumetti. They can’t imagine it as a

foreign movie shot in Parpland. It hits

a cognitive wall. I bet if some famous

person told them it was okay or clever, everybody would flip their perceptions

and enjoy it.

As

the lead I chose my friend Jody Hudson, who had a very expressive poker face,

like Buster Keaton—showing a lot of emotion with minute variations of

expression.

I

didn’t plan, I just began. I would have

to make up the movie as I went along. I

would shoot whenever Jody and I were both available, and grab other actors and

sets as best I could.

I had

a story vaguely in mind, but I started with a classroom scene somewhere in the

middle of the story. This was because it

involved a large cast and had to be shot in an empty classroom, and so it had

to be done on a weekend.

~ Making movies ~ ![]()

![]()

THE FIRST SLOCUM SHOOT

I rounded up actors at Sunday lunch-- whoever could

spare an hour or two. I just went around

the tables and asked who wanted to be in the movie. We went to a basement classroom in Trotter

Hall. I arranged the actors according to

when they had to leave: I would shoot the full-room shots first, then the kids

in front could leave as I narrowed down to the back rows, where I put the

actors who could stay longer.

So it had to be shot out of order, and there were

two sequences to keep in mind— the sequence of the intended final story, and

the sequence of who had to leave when, which governed the order of the

shooting.

I made up the story as I went along, starting with

this basic idea: the hero, in a boring

class, makes eyes at a girl in the front row, and his chair falls over.

Fleshed out as I shot, it went like this: the

lonely hero (Slocum Furlow, played by Jody) sits doodling at the back of a

classroom. The class is an idiotic mix

of philosophy, sociology and nonsense. As the discussion drones on

meaninglessly, Slocum catches the eye of a girl in the front row (played by

Carolyn Shields). They make eyes at each

other. He leans further and further back

in his chair till he falls over, very very gradually. Everyone leaves. The girl is gone.

The result of that shoot was electrifying.

Somebody New

~ Making movies ~ ![]()

![]()

Something

happened to me as I shot that first scene of my film, that afternoon in Trotter

Hall. My absent-mindedness and

scattermindedness disappeared. I figured

everything out in the moment, and made up the story as I went, keeping track

with surprising clarity of what was done and what was not. I had never been so clear-minded. I still had to keep making notes on the back

of my hand, but I was awake and alive in a new way.

As

never before, I kept all parts of the problem in my mind, working very

fast. I will never forget the clarity

and the excitement of making up that scene as I fought the clock, positioned

and directed the actors, took the shots, dismissed the actors, and narrowed

down to only Slocum. I became a

different person.

I HAD

SUDDENLY BECOME THE PERSON I ALWAYS WANTED TO BE.

And I

have always wanted to be that person again.

~ Making movies ~ ![]()

![]()

![]()

The Ceiling Flies

Away:

Slocum Rushes, May 1959

I kept

shooting “The Epiphany of Slocum Furlow”— a scene every two or three days— but

it took a week for the first rolls to be developed. I called in some friends to look at what I

had shot.

I

didn’t realize that most people can’t see a scene out of order and understand

it in their mind. Here is what they saw:

strange repeated shots of people lounging around and saying (silently) “parp

parp”, and repeated shots of Jody falling down in his chair. Even though I explained the scene to them

before running the projector, they were utterly mystified.

They

didn’t know.

But

for me, the roof flew off the building. I heard a roaring wind. My destiny had found me.

What

I saw was the finished scene as it would be.* The scene was atmospheric. It developed characters. It had a plot. It was moderately subtle. It was rather funny. And it was warm—more like a foreign than an American film, like the films of

Pagnol or Satyajit Ray.

* The finished scene—“Slocum Furlow Scene 7, The

Classroom” may currently be found on YouTube.

Most people don’t like it because there’s no lip-synch

(as in Huckleberry Hound)-- an unrecognized genre. If somebody famous said it was funny,

everybody would suddenly appreciate it.

It

was far better than I had imagined it could be, far better than I had remotely

hoped.

Hero Slocum exchanges

glances with the girl in the front row. From “Slocum

Furlow Scene 7-- The Classroom”, currently on YouTube.

The

question was not whether I could learn to make films. I already knew.

I was

a natural. This was what I had been put

on earth to do. Partly to make movies,

and partly to be again that person I was when I was shooting. This was no longer about being Best at

anything. This was about my heart, which

I had found.

I was

a natural. This was what I had been put

on earth to do. Partly to make movies,

and partly to be again that person I was when I was shooting. This was no longer about being Best at

anything. This was about my heart, which

I had found.

The

only problem was that I wanted to be an intellectual too.

…

![]()

Chapter 7.

THE

EPIPHANY OF TED NELSON

In that first year at Harvard, 1960=1, I took a

computer course, and my world exploded.

What would Freed

Bales have said? 1960

Freed Bales (he didn’t use the “Robert” socially) was a

most amiable and pleasant psychologist in my Soc Rel department. His long-term research included a gut course

that could be taken any number of times by undergraduates and grad students

alike, in which they argued about interpersonal issues at any level of inanity

they chose. Meanwhile, behind one-way

glass, Bales’ research assistants were taking down and coding everything that

happened.

Bales made the most trenchant remark on computers I ever

heard.

‘The computer is the greatest projective system* ever

created’, Bales said to me. Meaning that anyone looking at the computer would

think they were seeing reality, but would see something projected from their

own mind.

*A projective system is something which, like a Rorschach

test, invites people to project on it their own personalities and ideas, often

unwittingly.

For fifty years since then, I have marveled at how

everyone projects onto the computer their own issues and concerns and

personality.

I did too.

![]()

![]()

A

Wild Surmise

Then felt I like some watcher of

the skies

When a new planet swims into his

ken;

Or like stout Cortez when with

eagle eyes

He star'd at the Pacific--and all

his men

Look'd at each other with a wild

surmise--

Silent, upon a peak in

John Keats

I was

the first person on earth to know what I am about to tell you. I believe I thought of everything here in the

fall of 1960, though some of it may have been in 1961, the second semester of

that school year (before the summer of ‘61). I believe this can all be

confirmed from my detailed notes of those days (though they will likely be

telegraphic summaries and proposed articles to write explaining the

ideas).

No

one told me or suggested these ideas. I

didn’t read them, and there was no one to confirm them with. (A few conversations with computer scientists

on campus made it clear they had other obsessions.) But I didn’t need any confirmation. From all my background and daring, in media

and in ideas and initiatives in many directions, I simply knew.* I saw the vastness of what I was facing, and

the certainty of a new world to come.

* A longer list of reasons is given in Appendix 3.

A few

words, a few pictures of people at computer screens, and the understanding that

computer prices would fall—these gave me all I needed to know, a crystal seed

from which to conjure a whole universe.

And a good one. The only issue

was how to shape the real world toward that good, because it could all go wrong

in so many ways.

• They Had Been Lying

The

public had been told that computers were mathematical, that they were

engineering tools. This misstated things

completely. The computer was an

all-purpose machine and could be whatever it was programmed to be. It had no nature; it could only masquerade. The computer could become only whatever

imaginary structure people imposed on it-- onto which they would project their

own personalities and concerns.

Therein

lay the glory and the difficulty.

![]()

This mathematical stereotype of the computer would

continue to confuse everyone for decades—not just the public, but people in the

industry as well, under the weight of their traditions.

The computer could handle text; alphabetical characters

fit into the same memory slots as the numbers. Instead of adding and

subtracting them, you could move them around.

Text can be stored. Text could be

printed. Text could be shown on

screens. So far that was only done for

technical purposes, but obviously there was no limitation on what text would be

shown and how it might behave.

The computer did not contain ‘knowledge.’ Instead, it had to be programmed to simulate

some unified arrangement of data. This

data had to be represented by a lot of pieces of information placed in a lot of

memory locations. Suitably organized,

probed and updated, this collection of factoids could be made to appear as a

unified body of information, but this too was a masquerade. (The term “database” did not yet exist.) The editorial problems for a collection of

data—keeping it updated and consistent-- were just like the editorial problems

of a research paper, just more formalized and pretending to more rigor.

There was no magic to this simulation of

knowledge. It just took diligence and a

lot of work, and a lot of choices about conventions and standards and

consistency and authentication. The

implicit choices made all over the paper world—by librarians, office

supervisors, clerks, everybody— had to be made explicit and locked into

software.

• Computers Were Electric Trains ;

This Meant Personal Computing

INSIGHT: Computers were electric trains! Why did guys like electric trains? Because you can make them do things—plan them

and build them and watch them go around!

The computer

aroused all the same masculine desires to control and to putter.

I

wanted a computer; that told me every guy would want one. (The one I lusted for at the time was called

the AN/UYK-1, was highly reliable and was narrow enough be lowered into a

submarine through its hatch, and cost $75,000. But obviously the price was

going to come way down.)

* Unfortunately this costfall took far longer than I

expected.

And

if every guy wanted one, that meant there would be a huge personal computer

industry. When they got cheap enough, of

course.

• The Future of Mankind Was at the Computer

Screen

So

much of modern life was about paper and its manipulations. But it wasn’t the paper that mattered, it was

what was on the paper, and that could

be turned to data.

It

was obvious to me that for all clerical purposes and for all information, the

interactive computer would become the workplace of the future.

• Eliminating Paper

It

likewise seemed obvious to me that paper would be completely replaced.

![]()

The idea of “the paperless office” is widely derided

and called an impossible myth. I totally

disagree: it’s entirely possible. But

paperlessness is impossible the way they’re thinking of it. Today’s systems imitate paper! You can’t

have a paperless office unless you go to completely different representations

and rich connective systems.

We may compare simulating paper to the swimmer holding

onto the side of the pool—there will be no progress without letting go of it.

But

offices were hardly interesting to me back then. What mattered to me was how papelessness

could contribute to the creativity, the understandings, the intellectual

excitement of human life.

• Magic Pictures to

Command

Diagrams,

maps, history, every subject (and the connections between subjects) could all

interact on our interactive screens.

The

problem was working out the rules.

Everyone

should be able to contribute to a great world of interconnection, but not to

wreck it. How could this be set up?

…

• Splandremics

![]()

![]()

![]()

I

needed a word for all these ideas.

(It

did not come soon. Sometime in spring

1961, I think, I came up with splandremics. By which I meant—

• the design of

presentational systems and media

• the design of

interactive settings and objects

• establishing

conventions and overall frameworks for these designs

The

place where you would work—your screen setup and computer, or whatever else it

would contain—I wanted to call a splandrome.

Nobody

could imagine what I was talking about.

*It started with the "spl-" pseudo-morpheme,

which connotes splintering, and splendor, and other outgoing situations. And “emics” from “phonemics” and

“morphenmics.” And it sounded good, I

thought.

![]()

In the nineteen-seventies, I came

up with the word fantics, from the

Greek root meaning "show" that also gives us "fantastic"

and "sycophant." By which I

wanted to mean "all aspects of the art and science of presentation. " Nobody could relate to

that either.

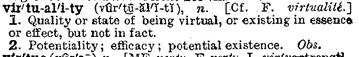

In the nineteen-nineties I started

using the term virtuality, which

correctly means the opposite of reality—the

design and abstraction of imaginary worlds. My old* Webster’s dictionary puts

it this way:

Unfortunately Jaron Lanier’s

popularization of Artaud’s term "virtual reality" has taken all the

oxygen from the word “virtual”-- many people use the term "virtual"

for 3D, literal 3D. This is an

unfortunate loss of an important meaning.

* I think Merriam-Webster 1905;

regrettably not on hand as I write.

• New

Non-Sequential Tools

Being

able to hold ideas in new structures meant we wouldn’t have to make them just

sequential or hierarchical any more. This had ramifications in every direction,

and it created many more directions, too.

I wanted

to make movies, but the idea of a fixed script pissed me off— so much happened

while you were shooting, in the inspirations of the moment, and so many ideas

might come later. What I wanted was a

way of holding movie scripts that would show a number of alternative

possibilities, and make it easy to rework the structure as scenes were shot.

![]()

I had not at the time thought of the word possiplex.

• New

Non-Sequential Media

We

could have texts that branch and interpenetrate.*

* By interpenetrate I mean transclude.

![]()

I had not at the time thought of the words hypertext and hypermedia.

Why

should a movie have only one ending? If

we could handle possiplexity, we could have movies that branch.

• Ideas in

Flight

We

could free text from rectangularity and sequence; this meant we could free

readers and writers from the constraints of paper and of typesetting. (How silly it was to have ‘space limitations’

on an article, when it could go on and on! The point was to have some new way

to organize it so the reader could grasp the whole in digest or overview form,

then take a long or winding route depending.

But there had to be a literary structure that made this clear.)

We

would be freeing both reader and author. The author would not have to choose

among alternative organizations; the reader could do that, choosing among the

author’s different organizations and perhaps adding his own. (What system of order would allow this was

still not clear.)

We

could also free up the educational system. If readers could choose their own

paths through a subject, they would be far more interested (as had been my own

college experience, skimming and flipping excitedly rather than slogging

sequentially). The educational system

could still have tests and strong criteria of learning; but we could give the

student freedom to choose the means and

style of learning a subject. This

would be a very powerful motivator. (It

had been for me.)

![]()

Unfortunately, pre-college education as we know it (and

inflict it) is a bureaucratic system for fulfilling lists-- scheduling seats,

classrooms, student movements, teacher movements, and tests. It is intrinsically and deeply hostile to

what I am talking about here.

• Parallel

Documents

While

I was learning to write in high school, I had been boggled by the number of

different possible ways to organize any piece of writing.

But

in a suitably general new medium, the structure could represent those

alternatives all at once, for different readers, and so the author would be

freed from having to choose among many

bothersome alternatives.

For

instance, in a conventional history book, the author must choose a sequence to

present events which were actually happening in parallel. In conventional writing, these go into

different chapters, or have sentences that effectively point to the different

event-streams. But if we can have

parallel document structure,* the different event-streams can be in different

text streams, coupled sideways; this structure should make clear all the

relationships to the reader.

* I am not sure that the genre of parallel documents

occurred to me in the 1960-1 period.

• The

Manifest Destiny

of Literature

Obviously,

writings like this would be far superior to ordinary writings on paper, and

nobody would want the old forms or writing any more. But of course the old writings themselves

could be brought forward as re-usable content for this new genre.

Nonsequential

writing—the term “hypertext” had not yet been coined—was obviously the manifest

destiny of literature.

I

foresaw a sweeping new genre of writing with many forms of connection; and of

course that was the genre in which I would want to create all my own works of

the future.

![]()

Any reader who still thinks these ideas have any

resemblance to the World Wide Web should probably take a hot bath.

But

it was vital that this new literary genre would have to be simple, clean,

elegant and powerful.

I saw

this as the manifest destiny of literature.

I

still do.

![]()

In case the reader doesn’t get to that point in the

book, I would like to acknowledge here that this design was finished, or

perfected, by Gregory, Miller and Greene in 1979-80.

Because of numerous political setbacks, described

later, I have had to abstract out a simplified version, which is the present

Xanadu design—implemented in 2006 as XanaduSpace, and (at this writing) pending

implementation in a client version in Flash or Silverlight.

• The Vast

Publishing Network

Obviously,

the future of publishing would be publishing on line.* A publishing house would have a system of

servers (a term not then in use) and vast storage to hold its offerings.

* I don’t think the term “on-line” existed yet, or even

the concept. However, “data

communication” at that time was already in use by the military and for air

traffic control, so the idea seemed obvious to me.

A

request for a particular document—or part

of a document-- would have to go to the publisher of that document. There would have to be some system of

payment, whereupon the content would be delivered.

(Some,

like a certain vicious journalist, have implied that I could not have known in

1960 that a world-wide electronic publishing system of interconnected documents

could ever be possible. That is

ridiculous. Data transmission was in the

air, it was discussed everywhere. It was

not standardized or generally available, but it was going to happen in some

form, and whatever form it came in, I intended to use it.)

• Self-Publishing

I

believed passionately in self-publishing, and still do. The publishing industry has always catered

to, and been run by, the shallow, conventional, pompous and smug, with

attitudes generally obtuse and behind the times. I wanted to free authors to publish on an

even footing with big companies.

My

great-grandfather self-published his poetry. My grandmother self-published her

poetry, novels and drawings. I had

self-published in college and intended to go on doing so, but this would be the

real way to do it.

![]()

(I have generally self-published out of choice [various

bitter anecdotes omitted]. If

self-publishing was good enough for William Blake, Samuel Taylor Coleridge,

Richard Burton the explorer* and T.E. Lawrence, it’s good enough for me. The revenue is a lot less but I there’s no

need to fight with editors, to compromise or dumb down.)

* Richard Francis Burton.

• Copyright and

Royalty

This

system of on-line publishing could not be free. Publishing has always been a

system of commerce (what’s the alternative, the government?)

I

already knew a thing or two about copyright, principally that

• it was a pain in the neck to get reprint permission

•copyright would not go away, being thoroughly

entrenched in the legal system.

The

question was how to transpose copyright to this new world of on-line electronic

documents, and whether this transposition would be beneficial and benign, or

ugly and clumsy and forbidding.

A

micropayment system would be needed— not just for whole documents, but for

little pieces of documents. Why should

you have to pay for a whole document—especially since documents might go on

forever, since there were no space restrictions?

…

• New Kinds of

Anthology

The

heartbreak of intellectual life is that there is no time to read

everything. Since boyhood I was sad that

there was no time to read everything— and so many wonderful books and articles,

more every day.

Textbooks

and anthologies try to help. They show

us see quotations, and excerpts, but we get no sense of the whole documents

they were excerpting. Every quote is

cut off from its original.

But

now, in this new world, anthologies could be different. Every excerpt would stay connected to its

original context! Whenever you wanted,

you could step from the excerpt to the original!-- and browse, and delve.

This

would be a total change in study and learning, especially of history and

literature. It could deepen our

understandings of everything. We would

think less in stereotypes.

• A

Movie Machine!

The

computer was obviously a movie machine.

What

are movies? Events on a screen that

affect the heart and mind of the viewer. What would the computer present? Events

on a screen that affect the heart and mind of the viewer—AND INTERACT! The movie screen would fly into this new

dimension of interaction, but the fundamental issues were the same: the heart and mind of the viewer. And who knew these better than a movie

director?

Interfaces

and interaction are not “technology.” They are movies.

This

was not about technicality; it was about the user’s experience, to which all

technicalities were subservient.

![]()

Many tekkies want to believe that “interfaces” are a

branch of computer science. They are

not. They are a branch of movie-making,

because they are all about what the user thinks and feels, and inviting the

user to think certain ways (understanding menus, for instance) and feel a

certain way (excited and participatory, rather than oppressed).

![]()

Only lately (ca. 2009) has the true issue

been made manifest in the computer field, with a new slogan expressing my views

of the last fifty years: User experience

design.

• A

Philosophy Machine!

The

computer was obviously a philosophy machine.

What

is philosophy? The search for the best abstractions.

What

was the fundamental problem of the computer? The search for the best abstractions. Everybody in the field was taking initiatives

in different directions, looking for the best fundamental units, the best

fundamental methods. It was philosophy

written in lightning.*

* I allude here to a famous remark on seeing

This

is not a technical issue, but rather moral, aesthetic and conceptual. Finding the right abstractions is the deepest

issue, and computer scientists wrangle endlessly over it.

It is

also a political and marketing issue: because eventually the different

abstractions—call them, say, “Macintosh” and “Windows”—fight it out in the

marketplace. This is marketing and

politics.

![]()

I thought that with my training in philosophical

analysis I was especially well-prepared for this issue, and perhaps I was, but

getting political leverage was quite another problem. I knew it would be but that did not

help.

• Doing it Right,

on the Cheap

I had

the mentality of a low-budget filmmaker: the right way to get this going was without

backing, because backers want to change things and it’s always a fight. (I had seen this personally in my father’s

fights with sponsors over the details of TV shows, right up till air time.)

But

there is nothing more powerful than an idea. Everybody said this and I believed